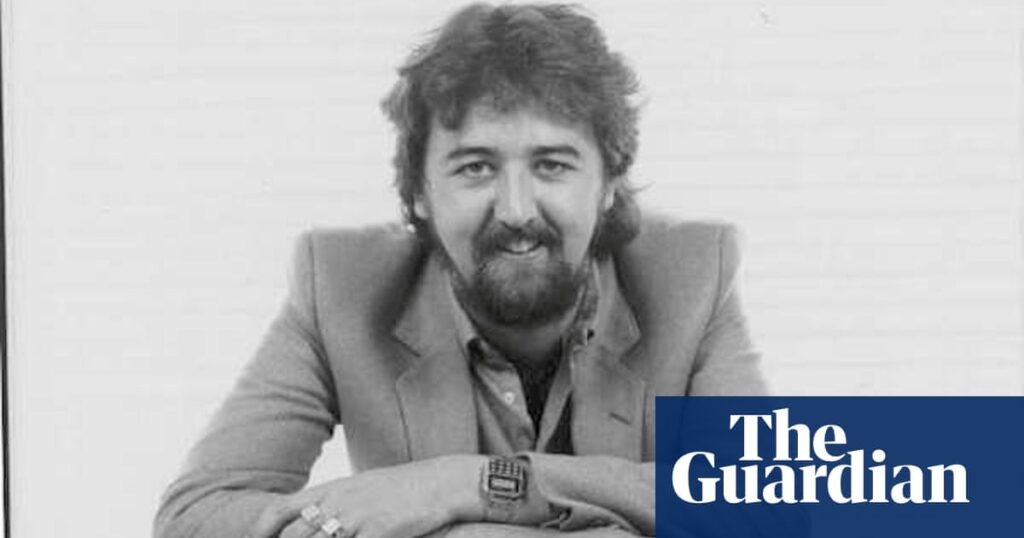

If you were a football fan who owned a computer in the early 1980s, there is one game you will instantly recall. The box had an illustration of the FA Cup, and in the bottom right-hand corner was a photo of a smiling man with curly hair and a goatie beard. You’d see the same images in gaming magazines adverts – they ran for years because, despite having rudimentary graphics and very basic sounds, the game was an annual bestseller. This was Football Manager, the world’s first footie tactics simulation. The man on the cover was Kevin Toms, the game’s creator and programmer.

The story behind the game is typical for the whiz-kid era, when lone coders would bash out bestselling ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64 titles in their bedrooms and then end up driving Ferraris around with the proceeds. As a child in the early 1970s, Toms was a huge football fan and an amateur game designer – only then it was board games, as no one had a computer at home. “When my parents when to see my careers master, I said: ‘Ask him if it’s possible to get a job as a games designer,’” says Toms. “He told them: ‘It’s a phase, he’ll grow out of it.’”

He didn’t. Throughout the 1970s, he worked as a programmer on corporate mainframes and for a while he was coding at the Open University. “It wasn’t long before I realised I could write games on these things,” he says. “Actually, the first game I made was on a programmable calculator.” In 1980, Toms bought a Video Genie computer, largely considered a clone of the TRS-80, one of the major early home micros. “I realised I could write the football manager board game I’d been trying to make for years on a computer,” he says. “There were two major advantages – it could calculate the league tables for me and I could work out an algorithm to arrange the fixtures.”

The Video Genie never took off – but then Toms bought a ZX81 with a 16k RAM extension and ported the game to that. “In January 1982, I placed a quarter-page ad in Computer and Video Games magazine and it started to take off,” he says. “I can still remember the first letter arriving with a cheque in it. In the first few months I sold 300 games.”

At this time, the game was extremely basic – there were no graphics, just text. Players picked a team from a selection of 16 and then had to act as its manager: buying players, deciding on a squad, then tweaking the side as it went through the season. You started at the bottom of the old fourth division and worked your way up. Toms wrote his own algorithms to generate fixtures and also decide the outcomes of the matches based on the stats of the teams playing.

“The difficult part was the player attributes,” he says. “I gave them a skill rating out of five, but then I wanted a counter-balance that so you couldn’t just buy the best players and leave them in the side for the whole season – there had to be a reason to take them out. In real football, the more you use a player, the more likely they are to get injured, so I incorporated that. Each player had an energy rating out of 20 – it diminished as he played, and the risk of injury increased. There had to be a reason to bring the lesser players in.”

Toms also wanted to add long-term strategy and planning to the game, and this came in its most popular element: the transfer market. In the earliest versions of the game, you’d be offered the chance to sign one player a week, but that selection was randomised – you never knew who would be available. “Say you get a rating three midfielder come up and you need to strengthen your midfield: do you spend money on that or do you wait for a five-rated player who might not come for weeks? This generated pressure and fun.”

The key problem he faced was memory. The expanded ZX81 had just 16k of it, which made some aspects tricky – including team names. “It was long before all the licensing issues came along,” he says. “My problem wasn’t: do I need to buy a licence to use Manchester United? It was that there wasn’t enough memory to store the name. Every team name had to fit within eight characters, so I chose teams with short names like Leeds – although I did put in Man U and Man C. The players were mostly well-known players of the time – but again, with short names – which is why Keegan is in there. It’s crazy how little memory there was.”

Football Manager was first released in the early days of the gaming industry – copies were sold via mail order or at computer fairs. But by 1982, high street stores started to take notice of the emerging video game sector. “WH Smith got in contact and said, ‘We like your game, we want to stock it’, and they invited me down to London. They eventually placed an order for 2,000 units – the invoice for that order was more than I was earning in a year. About a month later, my girlfriend rang me at work and said: ‘Oh another order has come in from WH Smith, it’s 1,000 units.’ When I got home I realised her maths was pretty crap – it was 10,000.”

Toms left his job at the Open University and set up his own company, Addictive Games. The subsequent Zx Spectrum and Commodore 64 versions of Football Manager came with an added component: match highlights, which showed basic graphical representations of key moments, such as goals and near-misses.

“It was inspired by Match of the Day – they extract the most fun parts of the matches,” Toms says. “I purposely didn’t put a match timer onscreen, so you never knew where in the match the highlight was happening; you didn’t know how close you were to the end of the match, and whether there was time for another goal. This added to the tension – it was a critical part of the design. There’s also a slight pause between each highlight, and that also creates tension. It was very simple but it worked very well.”

The game was a phenomenon, appearing on bestseller lists for years. My friends and I had hours of fun just editing the team and player names. We all remember it now. “I didn’t realise the full impact for years,” says Toms. “There was no internet at the time – although I did get a few letters saying: ‘I played your game for 22 hours straight.’ Or: ‘I failed my mock O-levels because of the game.’” He also knew that football pros were playing, including Arsenal striker Charlie Nicholas and Spurs manager Bill Nicholson, as well as Harry Redknapp, who later had a role as a real-life mentor to a competition-winning Football Manager player in 2010.

Toms wrote several other management games afterwards, including Software Star, a simulation of the games industry. But as the number of Football Manager conversions and updates increased, so did the stress. Finally, he sold the company and got out of games, returning to business coding while travelling the world. In 2003, Sports Interactive, the developer of the Championship Manager series, acquired the name Football Manager and rebranded its own game under that title – and the name lived on.

But the game wasn’t quite over. Ten years ago, Toms got chatting to fans of his original game online and asked if anyone would be interested in a smartphone translation – Football Manager as they all remembered it, with the same basic visuals. The response was positive and, in 2016, he released Football Star* Manager on mobile. Recently, he upgraded it again and released a PC version. “People are enjoying it because it’s easy to play,” he says. “That’s inherent in my design philosophy – it must seem simple but have subtle depth or it won’t retain the interest. I’ve had people tell me they’ve played 500 seasons and they have £5bn in their bank account – the balance is clearly right because even with all that money they’re still enjoying playing. I’ve also had people who played the original buying Football Star* Manager for their kids to play.”

Toms has clearly rediscovered the spark that brought the original Football Manager into the world, 40 years ago. He has long-term plans for Football Star* Manager, and perhaps Software Star, too. “I’ve still got loads to do,” he says. “I’ve got far more aims and ideas than I have time to implement at the moment. I’m not slowing down. I should do, but I’m not.”