Variously described as an “architect, painter, novelist, communist and convicted fraudster”, Fernand Pouillon’s life was punctuated by abrupt reversals of fortune that might have sprung from the pages of Dickens or Dumas. Throughout an eventful career, he ricocheted from intoxicating success, to financial scandal, prison, exile and eventual rehabilitation.

In 1985, when Pouillon was in his early 70s, he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur by President François Mitterrand. Yet just over 20 years earlier, Pouillon found himself in custody awaiting trial on charges of corruption. As a prolific architect-developer who had designed gargantuan housing schemes in France and Algeria, he was accused of funding irregularities and violating laws contrived to keep the processes of design and construction separate.

Staging a hunger strike, he was moved to a prison infirmary, from which he escaped by shinning down a rope smuggled in by his brother. On the run for eight months, he was dubbed “France’s most wanted architect”, before, with exquisite sangfroid, he turned up by taxi to the Parisian courthouse on the day his trial was due to begin. Sentenced to four years in jail, he passed the time by writing Les Pierres Sauvages (The Wild Stones), a bestselling novel about the construction of the medieval Cistercian abbey at Le Thoronet in Provence. The protagonist is a master builder who overcomes exacting working conditions and sceptical peers by dint of sheer willpower.

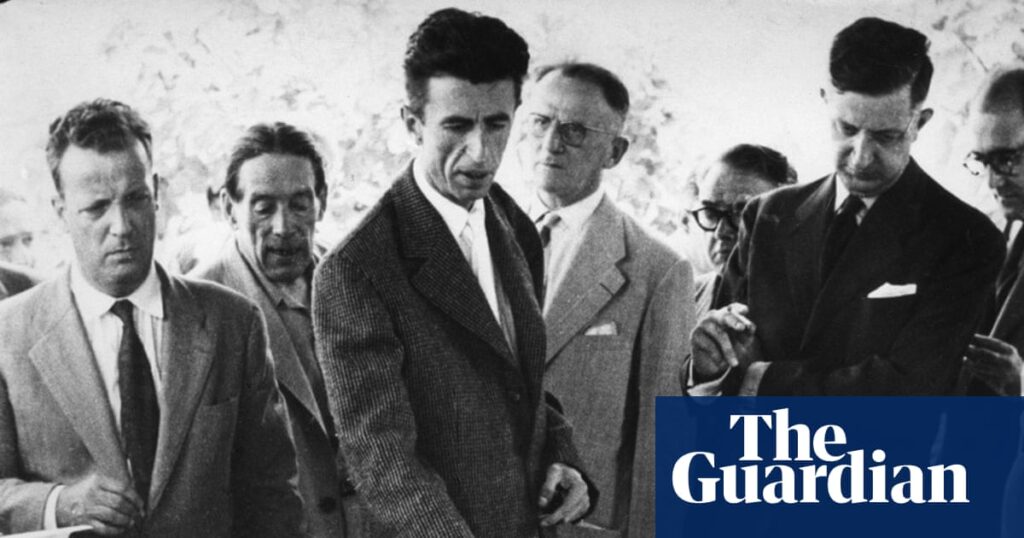

Known as “Pouillon le manifique”, Pouillon was an iconoclast who relished the trappings of success. At one point he reportedly owned a Bentley, an Alfa Romeo, two chateaux, townhouses in Algiers and Paris, and a yacht. Photographs of the time show a suave, sharply suited man, with a luxuriant quiff of jet black hair, like a Gallic Bryan Ferry.

His rise and fall is the subject of Fernand Pouillon: France’s Most Wanted Architect, a 2023 film by French documentary film-maker Jean-Marie Montangerand. “His personality and his antics overshadowed his work,” says Montangerand. “But his system was to build better, cheaper and faster than others so that everyone could live decently. He thought that beauty should not just be the privilege of the most well-off.” Showing for the first time in the UK, it examines Pouillon’s life and exploits, with current and historic footage of his housing in Paris, Marseille and Algiers.

Pouillon remains a divisive figure. But in spite of his entanglements, his architecture has endured, its qualities becoming more appreciated over time by users and critics. Attuned to the historic form and dynamics of cities, his buildings have come to be seen as a more nuanced alternative to the “brave new world” ethos of modernism.

His quartet of 1950s housing developments in Paris imitate the historic grain and texture of the city, with courtyards, loggias, gardens and promenades. And in the postwar heyday of concrete, he unfashionably favoured stone as a building material. “I hated the ugliness of render, the colour of concrete,” he declared in his 1968 autobiography. “For me, the century of reinforced concrete posed problems of appearance, of surface, of the skin of the building.” He favoured the creamy limestone of Provence, in its hefty, traditional, load-bearing form, as opposed to thin sheets clipped to a steel or concrete frame that constitute most of today’s “stone” buildings.

“Pouillon was a modern architect but he was not a modernist,” argue Adam Caruso and Helen Thomas, who compiled one of the first English language monographs on Pouillon, nearly 30 years after his death in 1986. “He was modern in the sense that Édouard Manet was a supremely modern painter: attentive to the history of art and to the inevitable and necessary continuity of culture, while at the same time being fascinated and enmeshed in the appearances and social mores of contemporary life that played out around him.”

What emerges from Montangerand’s film is a man driven by ambition, building at dizzying speed and volume in the often chaotic ferment of France’s postwar economic boom. As Pouillon himself put it, “200 housing units built in 200 days for 200 million francs”. Yet he disdained the rabbit-hutch mentality of modernist mass housing – the grands ensembles that were springing up in and around French cities. “Imagine the sadness of all the people who, after working all day, leave their offices to sit in their rooms as if they’re being punished,” he wrote.

Unlike Le Corbusier, the imperator of modernism, and a contemporary (though the two never met), Pouillon recoiled from theory and abstraction. For him, architecture was about building well and building efficiently, like the speculative developers of the Georgian and Victorian eras, optimising managerial processes and construction techniques to address specific economic and social needs. He understood the city as a network of public spaces, each with a different character to be experienced on the ground. “I build for the pedestrian, not the airplane captain,” he asserted.

His career first took off when commissioned to rebuild large tracts of Marseille, razed by wartime bombing and Nazi destruction. In January 1943 about 30,000 people were forcibly evicted from the historic Panier (“basket”) quarter housing immigrants and refugees, with 2,000 dwellings demolished by explosives.

Pouillon’s reconstruction respects and reinstates the area’s scale and street pattern. New housing blocks feature workshops at ground level and humanising details, such as balconies enclosed by timber lattices. Down by the Old Port, a series of long, stone volumes resembling 19th-century dockside warehouses extend along the Marseille waterfront, now the haunt of tourists and flâneurs who might never notice the small plaque placed on one of the walls denoting Pouillon as the architect.

Pouillon’s design skill and his ability to navigate between the competing interests of politicians, planners and bureaucrats caught the eye of the mayor of Algiers, Jacques Chevallier, who enlisted him to provide dwellings for the city’s expanding population, as opposition to France’s colonial rule intensified. Between 1953 and 1959, Pouillon oversaw the construction of three major residential projects, among them Climat de France, the largest housing project in north Africa at the time, with 3,500 dwellings designed to accommodate over 30,000 inhabitants structured around an expansive central square or maidan.

While Pouillon publicly disavowed colonialism, his buildings were nonetheless part of an impetus to subjugate the Algerian Muslim population. Ultimately, however, they were co-opted by the very people they were meant to control. Ringed by 200 three-storey high limestone columns, the monumental maidan at the heart of Climat de France became a familiar backdrop to political protest, from the Algerian war of independence to more recent confrontations during the Arab spring.

“People have gradually taken ownership of these spaces, transforming and repurposing them,” says Montangerand. “The children of Climat de France now proudly declare themselves to live in ‘the Pouillon city’. Architecture should be judged by the amount of life it allows to develop, which is why Pouillon’s work still resonates.”

Eventually released from prison in 1965, but shunned by the French establishment, Pouillon returned to Algeria, where he found a more receptive milieu in the country’s post-independence era, designing housing, universities, hotels and tourist infrastructure. In 1971 he received an official government pardon, a tacit acknowledgment that his downfall may have been politically as well as professionally motivated.

Aided by Algerian craftsmen, Pouillon’s final years were spent painstakingly restoring an ninth-century chateau in Belcastel in the south of France, not unlike his master builder protagonist in Les Pierres Sauvages.

When Le Corbusier died, his coffin was reverentially paraded through the courtyard of the Louvre accompanied by torch-bearers in military uniform. Conversely, Pouillon was not one for posthumous pomp. Today, he lies buried in Belcastel cemetery, in an unmarked grave. His many monuments are elsewhere.