The Trump administration has announced plans for continued military operations against Latin American drug cartels, following a US strike on a Venezuelan vessel that killed 11 people on September 2.

The United States has had a complex relationship with Venezuela, a country of roughly 30 million people, shaped by disputes over oil, politics and security concerns.

Nowhere is that tension more evident than in Venezuela’s oil economy: the country holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, yet today earns only a fraction of the revenue it once did from exporting crude.

How much oil does Venezuela have?

Estimated at 303 billion barrels (Bbbl) as of 2023, Venezuela is home to the largest known reserves of oil.

Saudi Arabia ranks second with 267.2 Bbbl, followed by Iran at 208.6 Bbbl and Canada at 163.6 Bbbl. Together, these four countries account for more than half of global oil reserves.

The United States, by comparison, holds about 55 Bbbl, placing it ninth globally. This means that Venezuela’s reserves are more than five times larger than those of the US.

Globally, proven oil reserves, which measure the quantities of crude oil that are economically recoverable with current technology, total approximately 1.73 trillion barrels.

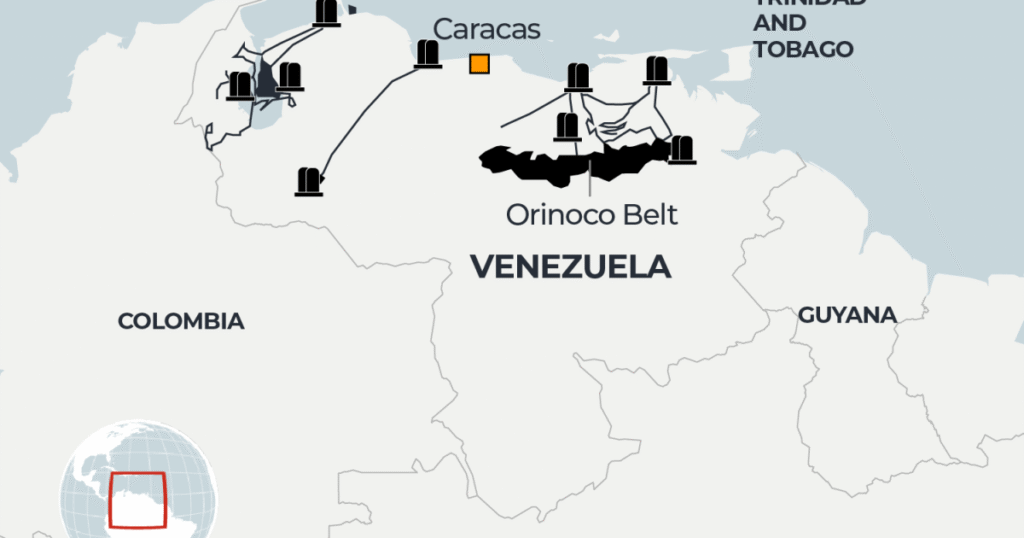

Where are Venezuela’s oilfields?

Venezuela’s oil reserves are concentrated primarily in the Orinoco Belt, a vast region in the eastern part of the country stretching across roughly 55,000 square kilometres (21,235sq miles).

The Orinoco Belt holds extra-heavy crude oil, which is highly viscous and dense, making it much harder and more expensive to extract than conventional crude. Producing oil from this region requires advanced techniques, such as steam injection and blending with lighter crudes to make it marketable.

Because of its density and sulphur content, extra-heavy crude usually sells at a discount compared with lighter, sweeter crudes.

The country’s oil production is dominated by PDVSA (Petroleos de Venezuela, SA), the state-owned oil company, which controls most of the Orinoco Belt operations. PDVSA has historically faced challenges, including ageing infrastructure, underinvestment, mismanagement and the effects of international sanctions, all of which have limited Venezuela’s ability to fully exploit its vast reserves.

Venezuela has some of the cheapest gasoline (petrol) prices in the world, thanks to extensive government subsidies. As of September 2025, the price of 95 octane gasoline is 0.84 Venezuelan bolivars per litre, which is approximately $0.04 per litre or $0.13 per gallon. This is just slightly more expensive than in Libya and Iran, two other major oil-producing nations, where gasoline costs about $0.03 per litre or $0.11 per gallon. For comparison, the average price of gasoline around the world is $1.29 per litre or $4.88 per gallon.

How much oil does Venezuela export?

According to data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), Venezuela exported just $4.05bn worth of crude oil in 2023. This is far below other major exporters, including Saudi Arabia ($181bn), the US ($125bn), and Russia ($122bn).

In addition to crude, Venezuela exports smaller volumes of refined petroleum products such as gasoline and diesel, but these remain limited compared with its potential due to ageing refinery infrastructure, technical challenges and sanctions.

Why have oil exports dwindled over time?

Venezuela was a founding member of OPEC, joining at its creation on September 14, 1960. OPEC is a group of major oil-exporting countries that work together to manage supply and influence global oil prices.

The country was once a major oil exporter, especially after PDVSA was created in 1976 and foreign oil companies were nationalised. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Venezuela supplied roughly 1.5 to 2 million barrels per day to the United States, making it one of America’s largest foreign oil sources.

However, exports began to decline sharply after Hugo Chavez was elected president in 1998, as he reshaped the country’s oil sector, nationalising assets, restructuring PDVSA, and prioritising domestic and political objectives over traditional export markets. Political instability, mismanagement at PDVSA and underinvestment in infrastructure also led to falling production.

The situation worsened under President Nicolas Maduro, Hugo Chavez’s successor, when the Trump administration imposed US sanctions, first in 2017 and then tightened those in 2019. These measures restricted Venezuela’s ability to sell crude to the US and limited access to international financial markets, further reducing the country’s oil exports.

As a result, exports to the US virtually ceased, and Venezuela shifted much of its oil trade to China, which became its largest buyer, along with other countries such as India and Cuba.

Venezuela’s oil exports rise to nine-month high

Following more than three years without oil shipments, in November 2022, the US Department of the Treasury granted Chevron, one of the largest American multinational energy corporations, a short-term licence to resume limited oil production and exports from Venezuela. Chevron resumed some oil production and exports, but only at a limited scale, as the licence came with strict restrictions on the revenue generated from these activities.

In 2023, the Biden administration continued to renew Chevron’s licence, allowing it to carry out limited operations in Venezuela. The resumption of operations was part of a broader strategy aimed at increasing global oil supplies and pressuring Venezuela’s government to make political concessions.

While the licence allowed Chevron to resume its partnership with Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, the scope of operations remained limited by US sanctions, ensuring that the Venezuelan government did not directly benefit from the oil revenues.

With the return of the Trump administration in January 2025, after a successful bid for re-election, President Trump issued an executive order in March 2025, imposing a 25 percent tariff on all goods imported into the United States from any country that imports Venezuelan oil, either directly or indirectly. This measure was designed to put additional pressure on nations, such as China, Russia and India, that had been increasing trade with Venezuela despite US sanctions. The tariff aimed to curb the flow of Venezuelan oil into global markets while attempting to isolate the Maduro regime economically.

The tariff achieved limited success: India’s Reliance Industries stopped buying Venezuelan oil, but China continued its imports despite the threat of tariffs.

By September 3, 2025, Venezuela’s oil exports surpassed 900,000 bpd, the highest level since November 2024, marking a nine-month high. However, exports remain significantly lower than their pre-sanction levels.