Even before Sydney Sweeney became better known for being in the centre of an increasingly absurd culture war, the unavoidable campaign to make her Hollywood’s Next Big Thing was showing signs of fatigue. The Euphoria grad, who gave a resonant performance in Reality, scored a sleeper hit with glossed up romcom Anyone But You but audiences were more impressed than critics, including myself (I found her performance strangely stilted). There was little interest from either side in her nun horror Immaculate, and earlier this summer her incredulously plotted Apple movie Echo Valley went the way of many Apple movies (no one knows it exists).

Post-thinkpieces, two of her festival duds (Eden and Americana) disappeared at the box office and she now arrives at Toronto in need of a win. And what better way to achieve that by going for an old-fashioned awards play, taking on the role of alternately inspiring and tragic boxer Christy Martin. It’s a role that’s already been buzzed about for months (Sweeney has been busy laying the standard “gruelling physical routine” groundwork) and at a time when movies about female sport stars still remain thin on the ground despite a swell of interest in them off screen, it’s a needed push in the right direction. But, as perfectly timed as this narrative might be, Christy just isn’t nearly good enough, a by-the-numbers slog that fails to prove Sweeney’s status as a one to watch.

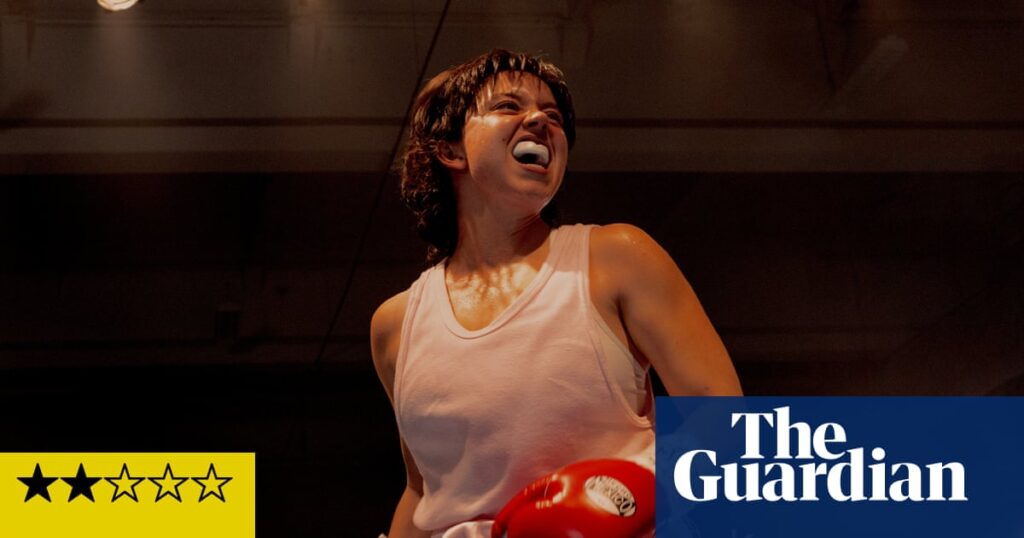

She’s a convincing force to be reckoned with inside of the ring, her training clearly having paid off as she confidently glides from fight to fight, but she can’t get us to believe in all that much outside of it, an actor still trying too visibly hard to make it all seem effortless (a few scenes with a more-at-ease Katy O’Brian, as another boxer, hint that she might have been the better choice). It’s a hefty ask, Sweeney playing the boxer over 20 years as she faced various struggles, and ultimately an impossible one too, her unsureness preventing us from getting beyond the film’s surface. Not that there’s much more here, though, despite the wealth of detail at play, Australian director David Michôd mostly sticking to the dog-eared playbook, at times that often make the film feel like Walk Hard but with boxing. There’s an excess of loudly soundtracked montages in the first act, yet with such little development outside of them we’re never quite sure what we should be feeling throughout, other than what we know from other boxing movies (it pales in comparison to last Toronto’s far smarter female boxer biopic The Fire Inside).

It’s a disappointingly rote way to tell the extraordinary life of Christy, who came from a mining family in West Virginia and found herself in the ring at a time when women weren’t seen there, a rise that sadly involved Jim Martin (Ben Foster), an older manager who takes her on as client and then wife, controlling her career and entire sense of self. Even as she became a groundbreaking name in boxing, as Don King’s first female star, her husband was there to bring her crashing back down to Earth. Over a fatiguing 135 minutes, we watch the rise and inevitable fall.

Michôd broke out with the blazing crime drama Animal Kingdom, but there’s none of that fire still burning here. The only real connection would be a continued interest in showing us the very worst of human behaviour, as we bear witness to Jim’s vile treatment of his wife. It has an obvious visceral impact, but in how he chooses to linger on his final act of unspeakably awful violence, it can feel needlessly explicit. We know the beats of a boxing movie and a domestic violence drama all too well and neither side of the story is told in a way that doesn’t feel overly reliant on cliche. Foster sticks to an overfamiliar odious mode (he might as well have been introduced with red flags) and while the excellent Merritt Wever is saddled with a one-note bad mum role, she does more with it than the film deserves from her.

Christy herself isn’t written with any more depth than a Wikipedia summary (Don King tells her in one scene that she has “some real personality” but where that is, I couldn’t tell you) and it betrays what could have been in smarter hands. The more uniquely interesting details of who she was – the wrestle between masculinity and femininity, how this played into struggles over her queerness and marital gender roles, how being crafted by a man turned her into a distrustful anti-feminist unwilling to recognise her groundbreaking impact and influence – are told to us in brief moments, but they never inform an otherwise ripped-from-a-TV-movie character. No wonder Sweeney struggles.

Christy Martin’s life was filled with devastating blows but in her biopic, we barely feel the impact.