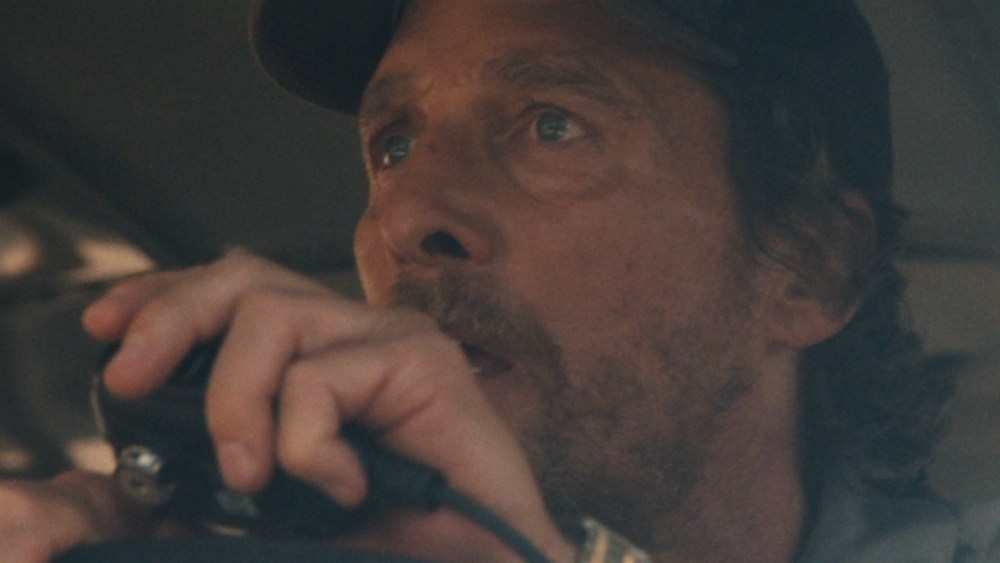

Eighty-five people died in the 2018 Camp Fire that consumed the town of Paradise, Calif., but the number could have been higher, if not for the bus driver who shepherded 22 elementary school children through the inferno. Witnessing how close they came to being burned alive and reliving the satisfaction of being reunited with their parents are the key reasons people might want to see real-life disaster movie “The Lost Bus,” but don’t underestimate the draw of movie star Matthew McConaughey. His character may be a real-life hero, but on screen, it feels like he’s the one making sure those kids turn out alright, alright, alright.

As directing assignments go, “The Lost Bus” seems ideally suited to Paul Greengrass, who might’ve had better offers to consider before 2020’s go-nowhere Western “News of the World.” Apple was lucky to get him for a sensational docudrama which lends itself to the “United 93” helmer’s immersive, eye-witness approach. It’s just that the angle, while inspiring, doesn’t begin to scratch what audiences want from a Camp Fire story — namely, the before and after of it all: Who, if anyone, were the corporate and civic villains responsible for the blaze, and how did such a community manage to rebuild?

On the latter front, Ron Howard got there first, and just as well, since he would have been the next most obvious director to handle such a project (which blends elements of “Backdraft” and “Thirteen Lives”). Co-written by Brad Ingelsby, “The Lost Bus” resembles several other Greengrass films in that it’s also slim on character (only one of the kids has a name and personality), but succeeds in plunging audiences into the action — which, in this case, means trying to steer an unwieldy vehicle through hell itself.

The director reunites with cinematographer Pål Ulvik Rokseth for a film that’s shakier and more radically handheld than their previous collaboration, the underrated but demanding “22 July.” It may have you reaching for the Dramamine — or simply turning away from the screen — even before the fires erupt, as Greengrass presents a normal day (the one immediately before Nov. 8, 2018) in Kevin’s life as if someone were writing a country song about him: His wife left him, his son hates him, his trusty dog has to be put down (no joke) and there ain’t nearly enough work to pay the bills.

Those details suit the Matthew McConaughey of it all, since the charismatic Texan star makes no effort to hide his accent and even goes so far as to cast his own mother (Kay McCabe McConaughey) and child (Levi McConaughey) as Kevin’s family in the film. Greengrass has always been scrupulously committed to authenticity, but here, he goes out of his way to include fire chief John Messina, dispatcher Beth Bowersox and other participants, playing either themselves or adjacent characters in the film.

Is the result more engaging or instructive than a documentary might have been? Maybe not at first, when Kevin is acting erratically, arguing with his ex-wife about what’s best for their son, Shaun. The boy called in sick from school on Nov. 7, and Kevin didn’t believe him, but on the day of the fire, Shaun is genuinely suffering and stuck at home. The whole time Kevin is rescuing those kids (without cell phone or radio service), he’s worried about his son’s well-being, which is more effective if you know it’s Levi in the role.

McConaughey is joined by one other name actor, America Ferrera, who plays Mary Ludwig, the schoolteacher whose charges Kevin was tasked with escorting through danger. She’s every bit as active a participant as he is, doing her best to keep the children calm and stepping up for a few of the more daunting tasks, like taking the wheel while Kevin directs traffic and searching for water during a dangerous pit stop. By this time, smoke has blocked out the sun (one girl asks whether it’s nighttime) and the grimy air has turned a glowing tumeric hue. One can only imagine what it must have been like to breathe.

The visual effects, by ILM and a handful of other vendors, are at once terrifying and awesome, apart from the lousy work done to reflect the accident that ignited it all (an iron hook that snapped on a Pacific Gas and Electric transmission tower, causing the live conductor to smash against the frame and shower sparks down on the dry brush below). Some of the broad-daylight visuals fail to convince, including early efforts by firefighters to reach the blaze before it can get out of hand, though the most important scenes — when the bus is engulfed in smoke and flames — look stunning.

Greengrass’ chaotic and occasionally hard-to-follow re-creation proves most thrilling about an hour and 45 minutes in, after the bus has been parked for a long, talky spell (Kevin discusses regrets about his relationship to his father, while Paradise-born and -raised Mary explains that she always considered the place safe, but now wishes she’d traveled more). The whole movie, Greengrass has been giving audiences the wildfire’s POV, propelled by high winds and blowing embers in all directions. Now it comes rushing through the clearing where they’re waiting for a break, and the two adults grab a fire extinguisher and spray it at fresh outbreaks.

Recognizing the futility after a time, they climb back aboard, team up to restart the overheated engine and go racing through a long stretch of burning road, surrounded on all sides by apocalyptic visions of burnt-out cars and collapsing homes. This is presumably the segment audiences will pay to see, and if they’re watching on Apple TV+, they can skip straight to this part. And yet, between when the film was greenlit and its premiere at the Toronto Film Festival, California has endured record wildfires. Fewer people died, but so many more lives were destroyed, tamping whatever pleasure there is to be had from “The Lost Bus” with a harsh helping of reality.