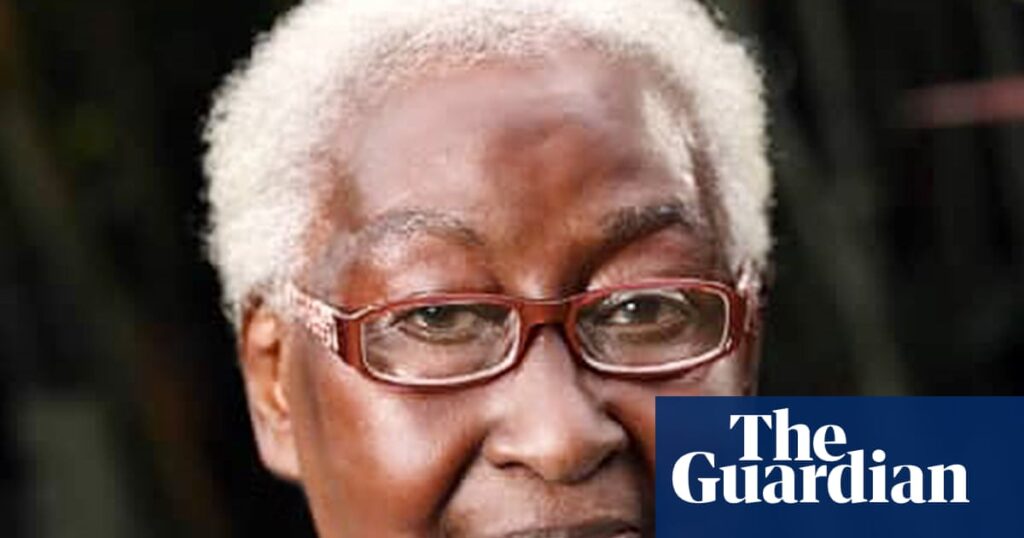

My friend Rhoda Kalema, a politician and women’s rights activist, who has died aged 96, was known as the “mother of Uganda’s parliament”.

When her husband, William, a minister in the government of Milton Obote, Uganda’s first post-independence leader, was murdered by Idi Amin’s thugs in 1972, Rhoda, though now a single mother of six children, decided to enter politics herself. In the interim government that followed Amin’s removal in 1979, she served as deputy minister of culture and community development.

In 1980 she was a founder member of Yoweri Museveni’s Uganda Patriotic Movement, and in 1989 was elected as the National Resistance Movement representative for the Kiboga district. In April that year she was made deputy minister for public service and cabinet affairs, and in that role helped reduce the number of ministries, implementing a recommendation from the World Bank. Among those abolished was her own – only fair, she said – although she continued to serve as an MP.

She was also a contributor to the new Uganda constitution drawn up in 1995. Retiring shortly afterwards from politics, she concentrated on her many other interests – the women’s rights movement, the Scripture Union and the interests of Kiboga, the home district of her husband.

The daughter of Veronica (nee Namuddu) and Martin Luther Nsibirwa, Rhoda was born into a patrician family in Buganda, a traditional kingdom then within the British protectorate of Uganda, where her father was the katikiro (prime minister). Veronica was the second of Martin’s six wives, and Rhoda was the 14th of his 27 children. She was educated at Gayaza high school and at King’s College, Budo, the first co-educational school in Uganda.

In 1950 she married William Kalema, a scholarship boy, and when he began studies in the UK, she joined him. Rhoda trained in social work at Newbattle Abbey College, in Midlothian, and then in social studies at Edinburgh University, and she visited the UK frequently over the years. On the Kalemas’ return to Uganda, Rhoda worked as a probation and welfare officer from 1958 onwards while her husband pursued his political career.

Her work on the rights of women in Uganda started in the 1950s, too, alongside activists such as Barbara Saben, Winifred Brown, Sarah Ntiro and Eseza Makumbi. She was a co-founder of the Uganda Council of Women (campaigning for changes to the law), got involved in Action for Development (working in rural areas with women who had little or no education) and was a founder member of the Forum for Women in Democracy (aiming for a just and fair society in which women and men participate equally).

My wife and I, former teachers in Uganda, first met Rhoda in 1973 at her son William’s graduation in Cambridge. We encouraged her to write her life story, which was published in 2021 as My Life is But a Weaving. On a return visit to Uganda, Rhoda showed us round the UWESO (Uganda Women’s Effort to Save Orphans) project to rebuild a school in Kiboga, with the bricks being passed along by a line of singing women and Rhoda in the lead, wearing a badge that read: “When women stop, everything stops.”

She is survived by three of her children, William, Veronica and Gladys, and by 10 grandchildren.