The paperback of “Straight Outta Scotland” by Gavin Bain, which tells the real-life yarn on which James McAvoy‘s directing debut is based, boasts a cover quote from the patron saint of working-class Scot-lit, Irvine Welsh: “One of the most amazing, high-octane, hedonistic morality tales of our time.” McAvoy’s take on the story of Bain (Seamus McLean Ross) and best mate Billy Boyd (Samuel Bottomley), who as rap duo Silibil N’ Brains briefly hoodwinked the UK hip-hop establishment into thinking they were California MCs rather than call-center employees from Dundee, is a little more housebroken than that.

But even though McAvoy, working from Archie Thomson and Elaine Gracie’s screenplay, domesticates the tale into a familiar but effective underdog narrative, it is by no means unworthy of the company. “California Schemin’” is perhaps a few degrees lower in octane-level than Bain’s book, and in terms of directorial verve, some way off Danny Boyle’s epochal adaptation of Welsh’s own “Trainspotting” — McAvoy hardly comes out of the gate as a great visual stylist, with DP James Rhodes’ pleasant but not especially memorable cinematography contributing to a slightly bland aesthetic, and the staging of certain scenes feeling scrappy and uncertain. But in the small areas of freedom McAvoy allows himself outside the main thrust of the familiar rags-to-riches-to-regret arc there are sharp little digressions and darker shadowy corners that suggest there’s more to the film, and to McAvoy as a filmmaker, than initially meets the eye.

But first, what meets the eye: Quiet, socially awkward Gavin and his more stable bestie Billy kick about the worn-down suburbs of Dundee with Billy’s funny, spiky girlfriend Mary (an utterly charming Lucy Halliday), dreaming of hip-hop stardom. After a trip to London — “Where the English are?” Mary gasps in mock alarm — ends in ridicule and rejection though, the pair hit on a scheme so ridiculous it just might work.

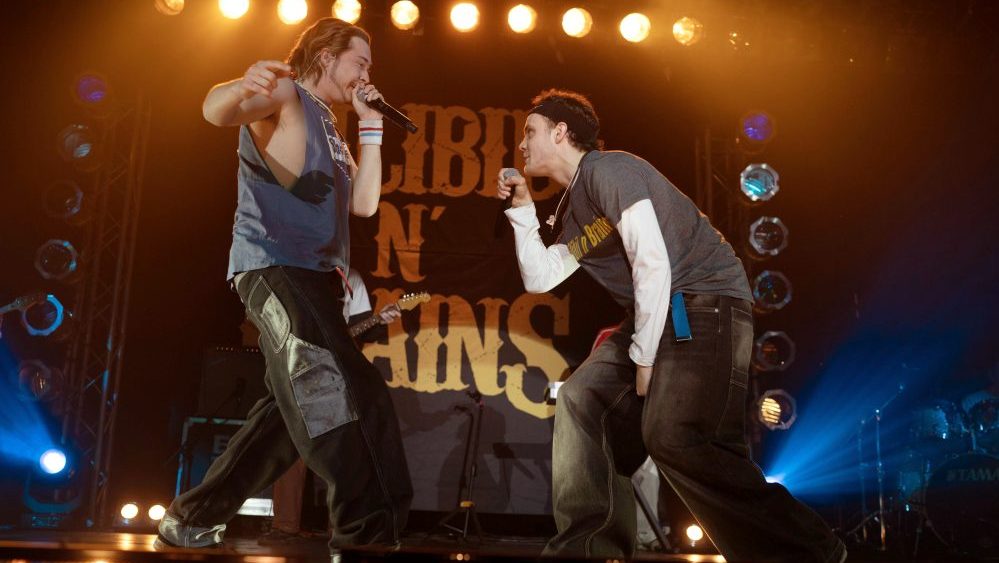

With every scout and label exec snickering poshly at their thick Dundee brogues, why not fake generic American accents and see how far they can get with the same material? Cue a montage of learning to “speak American” from movies and TV, including a decent imitation of Ross’ “We were on a break!” whinge from “Friends.” Now, Silibil N’Brains have new personas to unleash on an unsuspecting UK hip-hop world, which, in the person of fresh-faced newbie manager Tessa (Rebekah Murrell) and grizzled veteran Anthony Reid (McAvoy), head of Neotone records, is duly duped by their slouchy, yo-yo-yo facade.

Billy, Mary and Gavin take the remade Silibil N’ Brains’ early success as a hilarious prank, with Mary especially excited — from a distance — for the moment that, at the height of their duplicity, the pair will unmask their real identities and expose the music industry for its shallow, manipulative insincerity. But that moment, in shape of a coveted appearance on MTV, comes and goes, with Gavin, huffing the intoxicating whiff of cocaine-scented fame, reneging on the deal to reveal themselves at the last second. Billy reluctantly goes along with it, while Mary, watching far away in Scotland, folds her disappointment up like laundry and gets on with business of waiting for her two friends to snap out of it. Instead, Billy cheats on her and Gavin keeps doubling down on their scam, which gives the movie’s second half its jittery momentum. Gamble all you like in the game of fame, the house always wins.

What non-UK viewers might not appreciate is that the story unfolds specifically during a time in British media when RP (“received pronunciation”) was falling out of fashion with more youth-oriented broadcasting, and regional accents were starting to become more widely accepted — witness, for example, the iconically Geordie-accented narrator of the UK version of “Big Brother,” which began in 2000. It makes it doubly ironic that the hip-hop industry, with its emphasis on street-level authenticity, might have been so disdainful of Silibil N’ Brains when they rapped in their natural voices.

But as much as the film swipes at music industry hypocrisy, it is just as scathing about the peculiar sociopathy of success. Gavin, in particular, reveals an otherwise unsuspected vicious streak when it comes to protecting his precarious new status. It’s a bravely unsympathetic portrayal, considering Bain himself retains an executive producer credit, though it also suggests a certain degree of ventriloquism is needed to make ragged real life sound like breezy entertainment. McAvoy’s smarts in bringing out some of those unusual textures — also demonstrated in his own, viperish portrayal of label chief Reid — while the main engine of his movie chugs merrily away to an audience-friendly, exportable beat, is good reason to watch “California Schemin’” and better reason still to be curious about what he might deliver in future, working in his own voice.