Osmond ChiaBusiness reporter

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe US has dominated the global technology market for decades. But China wants to change that.

The world’s second largest economy is pouring huge amounts of money into artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics. Crucially, Beijing is also investing heavily to produce the high-end chips that power these cutting-edge technologies.

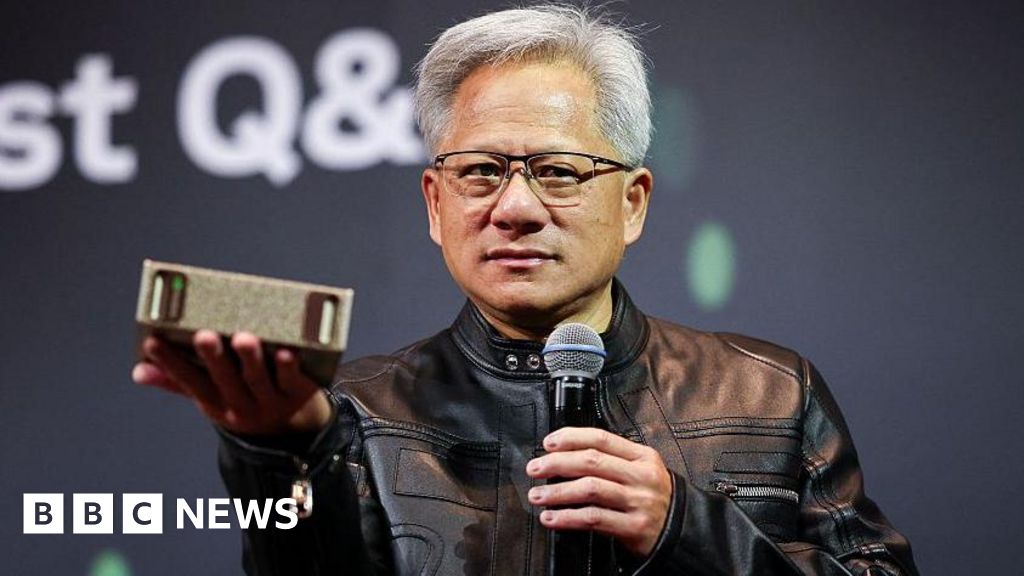

Last month, Jensen Huang – the boss of the global AI chip industry leader, Nvidia – warned that China was just “nanoseconds behind” the US in chip development.

So can Beijing match American technology and break its reliance on imported high-end chips?

After DeepSeek

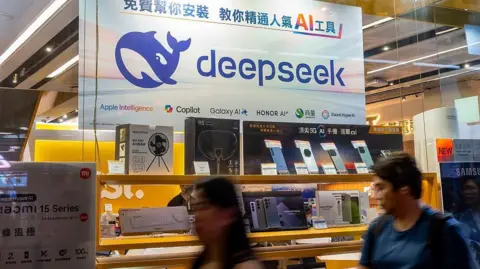

China’s DeepSeek sent shockwaves through the tech world in 2024 when it launched a rival to OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

The announcement by a relatively unknown startup was impressive for a number of reasons, not least because the company said it cost much less to train than leading AI models.

It was said to have been created using far fewer high-end chips than its rivals, and its launch temporarily sank Silicon Valley-based Nvidia’s market value.

And momentum in China’s tech sector has continued. This year, some of the country’s big tech firms have made it clear that they aim to take on Nvidia and become the main advanced chip suppliers for local companies.

In September, Chinese state media said a new chip announced by Alibaba can match the performance of Nvidia’s H20 semiconductors while using less energy. H20s are scaled-down processors made for the Chinese market under US export rules.

Huawei also unveiled what it said were its most powerful chips ever, along with a three-year plan to challenge Nvidia’s dominance of the AI market.

The Chinese tech giant also said it would make its designs and computer programs available to the public in China in an effort to draw firms away from their reliance on US products.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOther Chinese chip developers have also secured major contracts with big businesses in the country. MetaX is supplying advanced chips for the likes of state-owned telecoms operator, China Unicom.

Another hotly-tipped potential challenger to Nvidia is Beijing-based Cambricon Technologies.

Its Shanghai-listed shares have more than doubled in value over the last three months as investors bet that it will benefit from Beijing’s push for Chinese firms to use locally produced high-end chips.

Tencent, which owns the super app WeChat, is another notable tech giant that has heeded the government’s call to use Chinese chips.

There has also been no shortage of state-backed trade shows, promoting Chinese technology companies in a bid to attract investors.

“The competition has undeniably arrived,” a spokesperson for Nvidia told the BBC in response to queries about the recent progress made by Chinese chip firms.

“Customers will choose the best technology stack for running the world’s most popular commercial applications and open-source models. We’ll continue to work to earn the trust and support of mainstream developers everywhere.”

Yet some experts have cautioned that claims made by Chinese chipmakers should be taken with a pinch of salt due to a lack of publicly available data and consistent testing benchmarks.

China’s semiconductors perform similarly to the US in predictive AI but fall short in complex analytics, said computer scientist Jawad Haj-Yahya, who has tested both American and Chinese chips.

“The gap is clear and it is surely shrinking. But I don’t think it’s something they will catch up on in the short-term.”

Where China leads – and lags

On the BG2 technology and business podcast in September, Nvidia’s Jensen Huang highlighted the strengths of China’s tech sector, crediting its hardworking and vast talent pool, intense domestic competition and progress in chipmaking.

“This is a vibrant entrepreneurial, high-tech, modern industry,” he said, urging the US to compete “for its survival”.

His assessment is likely to be welcomed by officials in Beijing.

The country has long vied to become a global leader in tech, partly to reduce its reliance on the West.

For years, China has invested heavily in what President Xi Jinping calls “high-quality development”, which covers industries from renewables to AI.

Even before US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House, China had spent tens of billions of dollars as part of its efforts to transform its vast economy from the “world’s factory” for basic products to a home of cutting-edge industries.

An ongoing tariffs war with Trump’s America has only made that mission more urgent.

Xi has vowed to make his country more self-reliant and not depend on “anyone’s gifts”.

Mr Huang has also warned that the US should trade freely with China or risk handing it the edge in the AI race.

This comes against a backdrop of Beijing applying more pressure on Nvidia as it launched an anti-monopoly probe into the firm last month.

But China’s state-led approach can also be an obstacle to innovation if everyone in the sector only focuses on a “shared goal”, said computing professor Chia-Lin Yang from the National Taiwan University.

It can make it harder for disruptive ideas to break the mould, she added.

China’s chip industry has also yet to overcome criticism that its products can be less user-friendly than those of Western rivals like Nvidia.

Prof Yang believes these issues can soon be solved by China’s huge number of skilled tech industry workers.

“You cannot underestimate China’s ability to catch up.”

Getty Images

Getty Images‘Bargaining chip’ for China

She described China’s recent announcements about the chip sector as a “bargaining chip” in its months-long tariffs negotiations with the US.

Beijing aims to pressure Washington into selling its advanced equipment or risk losing its position in such a large market, said Dr Jawad.

These announcements project strength on China’s part, even though it is likely to still want to buy American technology, he added.

Most experts agree that China is still reliant on the US for the most powerful chips, at least for now.

Beijing needs access to some high-end American technology for its more advanced projects and to ensure it isn’t left behind, said semiconductor engineer Raghavendra Anjanappa.

Realistically, China can reduce its dependence on American chips in less-advanced tools, but doesn’t have the “raw performance” of US chips to train more complex AI systems, said Mr Raghavendra.

Despite a number of breakthroughs China still lacks the highly developed supply chains that have been long established in the US, South Korea and Taiwan.

The US has also deployed export restrictions as it tries to slow down China’s development of advanced technology, including Washington’s decision to block Beijing’s access to high-end Nvidia chips.

The US has “hit China exactly where its dependency is deepest,” said Mr Raghavendra.

“But China’s not far off in the grand scheme and they might only need five more years to be independent from the US.”