Subtitled Art and Independence, Nigerian Modernism is a complicated, contrary exhibition, tracing the development of modern art in Nigeria from the period of British colonial rule to the end of the 20th century. Focusing on individual artists and on various artists’ groups, it attempts a history of movements and of alliances in a country that has been both factionalised and divided by language and belief, religious and ethnic divisions, by the traumas of colonisation and of civil war. The sweep of Nigerian history, even over the past century or so, is too big and too complicated to be charted through the lens of the country’s art. What can modernism possibly mean here, especially from our position at the end of the first quarter of the 21st century?

European-style academic portraiture, including paintings by Aina Onabolu (one of the few women here) and by Akinola Lasekan, who also depicted Yoruba acrobatic dancers and mythic scenes, jostle with a pair of 1910-14 carved wooden door panels, depicting a British officer, carried in some sort of sedan chair, with shackled prisoners carrying his possessions, to be received by the Ogoga – or king – of Ikere. The officer looks, inadvertently, like a little homunculus on a bier. Nearby photographs, by Jonathan Adagogo Green, one of Africa’s first professional photographers, show the king of Benin, deposed in the brutal invasion of Benin City in 1897, shackled on board a British yacht, on his way into exile. The photographer is complicit in this scene, and in others where he was hired to photograph similarly deposed local rulers, dressed in all their finery.

All this is so much scene-setting. We jump to Ben Enwonwu (1917-94), who was described by the late curator and critic Okwui Enwezor as “arguably Africa’s first art star”. His tall, carved figures, commissioned by the Daily Mirror in 1960, the year of Nigerian independence, are a group of men and women reading newspapers, which seem to mysteriously transmogrify into wings. The readers are variously astonished and transfixed.

Enwonwu’s career as sculptor, painter and art educator wasremarkably varied. He painted the celebration of Eid and flamboyantly costumed ritual dancers; he sculpted a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II and made sinuous watercolours of silhouetted, naked dancing women, titling them Black Culture and Negritude (these, I think, have been a reference for British Nigerian artist Chris Ofili). Versions of Enwonwu’s sculpture Anyanwu, depicting an Igbo mythological figure, stand outside the Nigerian National Museum and at the UN building in New York. The small version here is in the Royal Collection. Enwonwu’s skill was, I think, mostly graphic, whatever his medium.

It is also easy to get mired in the sociology of groups of artists included here, though it is probably an unavoidable rubric. In 1960 a group of rebellious art students, rejecting the limited Eurocentric curriculum they’d been taught, first formed the Zaria Art Society – to whom a room is devoted – and moved to south-western Nigeria to co-found the Mbari Club of artists and writers alongside German publisher Ulli Beier.

Aesthetics and contingency both played their part. Many of the works in this close-hung room are very much of their period. There’s a flavour of the late 1950s, many of the artists favouring a kind of semi-abstracted, often tortured figuration not so removed from the kinds of things their counterparts in the UK were doing at the time, though some had more urgency and purpose.

Uche Okeke painted a monstrous bloated amphibian, and a genuinely nasty depiction of a Christian convert sacrilegiously unmasking an Igbo ceremonial dancer. Okeke’s raw and violent paintings of this time are matched by Demas Nwoko’s Nigeria in 1959 which shows three white colonial officers sitting together in great unease. Behind them loom five Nigerian soldiers, servants of the state, their faces shadowed and menacing in the gloom, Nigerian acolytes who imagined they had immense powers, whereas they had no aim and future. Until, of course, they found others to serve. The painting is like a premonition.

Large-scale photos of 1960s European modernist architecture are pasted to the wall in a section devoted to post-independence Lagos. Nearby hang a few Highlife album covers, while a playlist by DJ Peter Adjaye, is piped, too quietly, into the gallery. More could have been made of this. Meant as an evocation of cosmopolitan energy, the room itself is anything but jumping, in the same way that Tate Modern’s celebration of post-independence Lagos in its opening 2001 exhibition Century City failed to capture the city’s vitality, while also soundtracking the show with Highlife music and featuring the same photographs – by JD ’Okhai Ojeikere – of women sporting astonishingly sculptural hairstyles.

We take a quick respite in the sacred groves of Osun, near Osogbo, where Austrian-born artist, Yoruba priestess and senior member of the Ogboni cult Susanne Wenger (1915-2009) worked with local craftspeople and artists for more than 40 years to restore and extend the traditional reserve of deities, and set up what is called the New Sacred Art Movement. At Tate Modern, a group of diminutive sculpted figures sit on a low, green platform against the backdrop of a black and white photograph of part of the shrine at Osun, now a Unesco World Heritage site. The overall effect is deeply underwhelming.

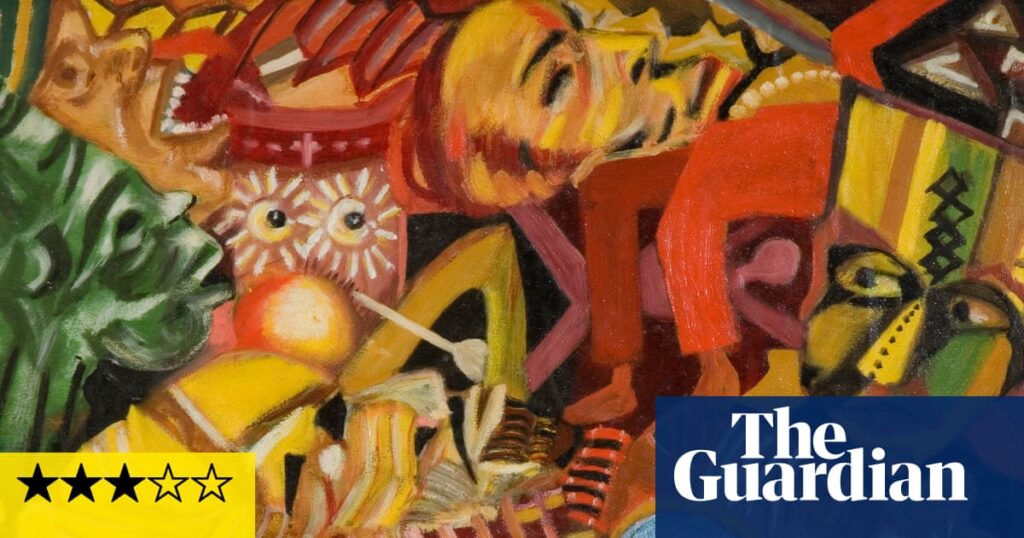

More interesting is the work of the Oshogbo School, based in Osogbo , a melting pot of cultures and beliefs, and now a centre for the Yoruba religion. Yoruba mythology and culture were at the heart of artist and musician Twins Seven Seven’s work. This guy had a remarkable life and is owed a biography; his complex, dense paintings, peopled by spirits and ghosts and fearsome creatures are electrifying. In one etching, heaving with pattern and swarming cityscapes of the imagination, he clutches at the city entwined in his fingers. It is called In the Palm of an Architect.

A reading of Come Thunder, by poet Christopher Okigbo, who died fighting as a volunteer for Biafra during a battle with Nigerian forces in 1967, fills the penultimate room of the show. “The smell of blood already floats in the lavender mist of the afternoon,” Okigbo wrote. “The death sentence lies in ambush along the corridors of power…” It is hard to listen to the verses, repeated on loop, as one goes from painting to painting, object to object.

Terrors and tremors are threaded through Nigerian Modernism, along with conflicting aspirations and the mess of history. Obiora Udechukwu’s monumental and strange 1993 work Our Journey, with its little figures, gatherings and events inscribed, faintly, on an unfurling spiral of yellow paint that crosses an otherwise almost abstract swooning fields of colour, punctuated by disruptions, sheerings and symbols, is full of questions and intrigue. The drawn, the painted and the symbolic are in constant flux.

Now in his 70s, Udechukwu is worth a room of his own here, but the final gallery is devoted to the paintings of Uzo Egonu (1931-96), who moved to the UK as a teenager. He returned to Nigeria only once, for two days, in the 1970s. Buses traverse Piccadilly Circus, as though seen in a fish-eye lens. People sit alone, reading. There’s some sort of clamour in a crowded room and people tussling with a ladder. Egonu’s paintings have an anxious sinister calm. His figures, imprisoned by geometry and oddly static, exist in a painted modernity that seems to defy any particular place or moment. The modern is inescapable. It is an oddly abrupt ending to an unfinished story.