Twenty years ago, the Guardian featured 10 newborn babies in countries across Africa, describing their births, their families and the environments they had been born into. We followed these babies at five-year intervals up to 2015 – the date the United Nations had set for achieving the millennium development goals – as a way to tell stories that might be those of millions of others across the continent as they worked to provide the best chance for their children.

Although some progress was made, the millennium development goals were not met by 2015 and that year UN member states adopted a new approach – the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development with 17 goals for ending poverty and inequality, while also tackling the climate crisis. With five years to go, only 18% of those goals are on track to be met.

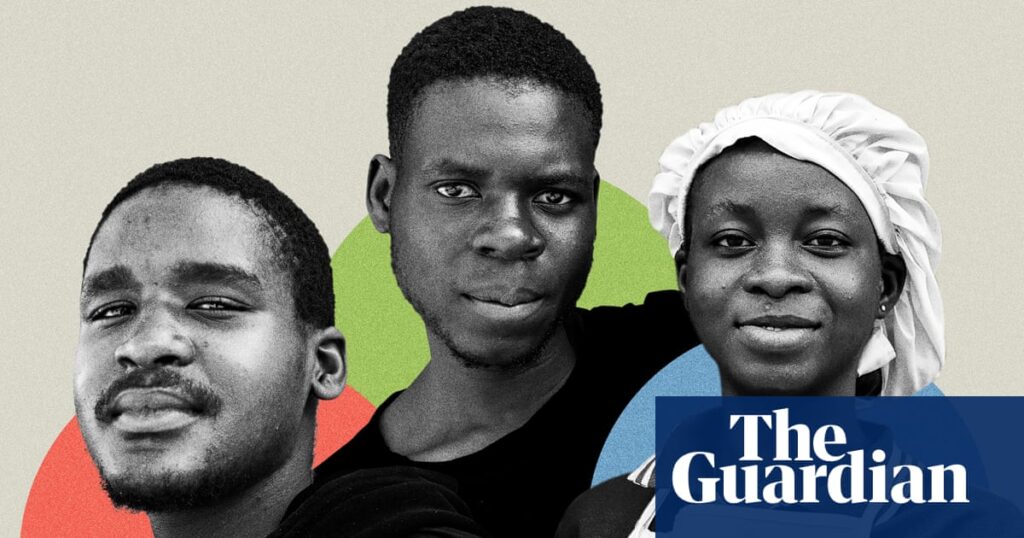

This year, the Guardian set out to track down those children born in 2005 to see how their lives were turning out. It took months of work and many proved untraceable; but we caught up with three – in Malawi, Ghana and South Africa. These are their stories.

Innocent Smoke – Malawi

Home for Innocent Smoke today is one room that he shares with his wife and baby in Mponela, on the outskirts of the Malawian capital, Lilongwe. The small agricultural town lies about 36 miles from where he was born in 2005.

With brick walls, a cement floor and a roof of corrugated iron, it is far more advanced than the straw-thatched hut where he grew up. He pays 15,000 Malawian kwacha (£6.50) a month in rent for his home, which has no running water or electricity.

In 2022, Innocent married Edess Gwalanya, 22, who grew up in a village two miles from where he was living with his parents. They met when Gwalanya was on her way to church; he asked her out, and they married less than a year later.

The couple’s first child was born in January last year but he died of heart problems a day later. Malawi has a relatively high infant mortality rate, with an estimated 29 babies in 1,000 dying before their first birthday.

“We were devastated as a family because we had accepted his arrival as a gift from God,” says Innocent. “But we were uplifted by the realisation that it was God who gave us the child and it was God who took him away. We are now happy that God gave us another child.”

Their second son, who is happy babbling away in the background, was born in January and is named Israel, after Innocent’s late grandfather.

Innocent, who has a certificate in motorcycle mechanics, has done a few jobs, including working in a shoe factory, as a cleaner at a school, a security guard at a hospital and on a farm. “I acquired the vocational skills because I could afford the fees for the training, but I have been struggling to raise resources to open my garage to repair motorcycles,” he says.

He is now working for a Chinese construction company that is renovating the M1 road, a key route that connects landlocked Malawi to the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam. The job involves testing soil and cement on the newly laid asphalt.

Innocent’s dream is to build a house for his family, but he says: “I am scared about my job security and possible unemployment. I am married and have a child, so losing a job is a terrifying prospect. The cost of living, particularly food, is very high, so one needs a job to survive.”

Unemployment among young people is high, with more than half of those aged 18-35 without jobs and looking for work. More than half of young people have considered leaving the country, according to the pan-African research network Afrobarometer.

The economy has stagnated for a long time, creating fewer jobs. For years, the economy depended on tobacco, but global anti-smoking campaigns have put the country’s biggest export under severe pressure.

The majority of Malawians are born and die in poverty. It is a reality that Innocent, a voter in last month’s presidential elections, is hoping can still be reversed.

“Candidates for leadership should have the right policies to fight poverty and make the life of people in the villages better. They cannot employ everyone but should make sure they create enough companies that will employ enough people so that we can reduce poverty,” he says.

“I voted for my preferred candidate,” Innocent says. “Someone who can change my fortunes as well.”

Golden Matonga in Lilongwe

Hannah Adzo Klutsey – Ghana

At 10, Hannah Adzo Klutsey dreamed of becoming a doctor, hoping to lift her family from poverty in Sapeiman, a suburb of Ghana’s capital, Accra.

Today, at 19, that dream has evaporated, replaced by the reality of baking cookies and layering buttercream on cakes in a makeshift shop in Ofankor Barrier, just outside Accra.

Hannah is thankful for her apprenticeship, but it is a far cry from her dreams. “Life pushed me here,” she says, wiping flour from a bowl. She divides her time between two worlds – learning how to make cakes during the week and returning to Sapeiman every weekend to her family to help with household chores.

“I wake up at 5am every day to help prepare the day’s orders,” she says, carefully packing the biscuits she baked earlier into plastic bags for sale. “We make wedding cakes, cookies and special pastries. I’m learning everything – from mixing the flour and butter to the final wedding decorations.”

Despite Ghana being one of the world’s leading gold and cocoa producers, the country’s economy hit rock bottom in 2022, causing its most severe economic crisis in decades and forcing the country to seek a bailout from the International Monetary Fund.

Until the Covid-19 pandemic, poverty in Ghana had fallen considerably. However, projections have worsened as households have been under pressure from high inflation and slowing economic growth. According to the World Bank, poverty is projected to rise, reaching 51.2% by 2027.

Hannah, who has a nasal growth and struggles with chronic headaches and difficulties breathing at night, is unable to afford hospital care and often self-medicates with pharmacy painkillers and herbal remedies.

Unlike many peers who are single mothers or married, Hannah does not have a husband or children. “I don’t even have a boyfriend,” she says with a smile. “My biggest dream is to make my parents proud.”

Her sleeping quarters are a cramped metal container that she shares with two other apprentices – Betty and Patience. Thin mats and second-hand blankets line the concrete floor.

The shop has no water or toilets, compelling them to beg neighbours for access to their facilities. “When nature calls, it’s torture,” says Patience. “If they refuse, you must walk to town.”

It has been three years since Hannah completed junior high school with “bad” final grades. She did not continue because she had problems with reading and spelling. Many of her classmates who continued their education will graduate from Ghana’s free senior high schools this year. Those with good grades will have the opportunity to enrol at university.

Hannah does not regret abandoning school and dismisses suggestions that she could be disadvantaged for not continuing with higher education. “I like what I am doing now,” she says. “I am proud of my parents and myself.”

She points out that while her peers are awaiting their exam results to determine their qualification for further education, she will soon finish her apprenticeship and open her own shop. “I’ll achieve more than them,” she says. “Some day, I’ll go to university to study catering.”

Hannah’s father, Benjamin, who makes a living selling sand, says: “Apart from her learning difficulties, education became too expensive so we decided to put her into an apprenticeship.” However, he adds: “Hannah’s apprenticeship is not cheap either.”

after newsletter promotion

She receives about 50 cedis (£3) a month from her parents to cover her needs, including food costs and all the ingredients she has to buy for her training. “We are really struggling to keep her in training,” says Benjamin.

Hannah sometimes cannot afford to buy food to eat, relying on small loans from colleagues or the generosity of her boss, Paulina. “They lend me money or give food,” she says.

But some days, no help comes. “Sometimes I don’t eat and I will sleep like that,” she says, adding: “I feel bad that my parents don’t have the money to feed us.”

Paulina praises Hannah’s progress, saying she will graduate in two months. However, graduation depends on payment of 3,000 cedis – a fee unaffordable for her parents, whose combined daily income is only 110 cedis.

Richard Sky in Accra

Angel Siyavuya Swartbooi – South Africa

Angel Siyavuya Swartbooi, or Siya, spent his 20th birthday in rehab. Now, exactly a month after being discharged, Swartbooi is convinced that his drug use is a thing of the past. “I’m not trying to stop,” he says. “I stopped smoking. I no longer smoke.”

And he is excited about his future. “I want to take this second chance,” he says. “I am grateful that my parents sent me to rehab.”

He is sitting on a plastic chair he borrowed from a neighbour in the nine-square-metre room his family has lived in since 2023. They moved to the relatively new township of Mfuleni to get away from the crime and drugs that are rife in Khayelitsha, the sprawling slum outside Cape Town.

“It is too small for the money we pay,” says his mother, Nonzuzo Swartbooi. “But it is safe and there are no leaks.”

Nonzuzo and Siya’s 14-year-old sister, Akhanyile, known as Aka, are lounging on the double bed that almost fills the room. It is cramped but it feels like a home: there’s a wall-mounted TV, a full-size fridge and a kitchen unit with a flaking melamine countertop.

A black-and-white photograph of a family of elephants hangs above the bed and there is a tub of laundry in the shower.

Siya’s father, Benson Ntsimango, lives in a flat nearby (his work as a chef means he keeps erratic hours), but he and Nonzuzo are still together and committed to creating opportunities for their children.

Nonzuzo, who works long hours in the fraud department of a mail-order company, says she knew something was wrong with Siya when he dropped out of school in grade 10, three years ago.

“We would think he was going to school,” she says. “After a week we would get a call saying he had not attended.

“When we got home we would shout at him and he would have too many excuses,” she says, adding: “I was really worried.”

Siya appears embarrassed talking about his drug use in front of his mother and sister. He says he started smoking cannabis due to “peer pressure” and insists he has never used anything other than cannabis and alcohol.

His mother does not believe him. “There is no way weed can make you that crazy,” Nonzuzo says but she has forgiven him. “That was not Siya,” she says.

“Most people around him were shocked. Even his teachers were so surprised. He was good in school,” his mother adds.

Things came to a head earlier this year. “He came home one evening and just stood there staring at us,” remembers Nonzuzo. “He was saying things we couldn’t understand, going up and down, from 7pm until 3 in the morning.” Eventually she called the police, and they took him to hospital.

While Siya was initially angry at his parents for sending him to rehab, he says he started to think more seriously about his future. After a few days in a local clinic, he was transferred to a larger facility and then to a dedicated psychiatric hospital.

In total, he spent three months in rehab, an experience he describes as “fun” (he especially enjoyed learning to meditate) despite missing his family. Nonzuzo made a point of only visiting him twice: “I wanted him to feel like what he’s doing is totally wrong.”

A study published in the International Journal of Drug Policy in 2024 suggests the number of South Africans taking illicit drugs jumped more than sixfold between 2002 and 2017.

Recent drug use was also “associated with having multiple sexual partners in the last year … experiencing psychological distress, and being less likely to have ever been tested for HIV”, the study found.

Since leaving rehab, Siya spends a lot of time at home alone, meditating on the double bed and entertaining the neighbours’ children. “He loves kids so much,” says Nonzuzo. Siya laughs in agreement: “I like spending time with kids, they are fun, they make me enjoy my day.”

Although the neighbours keep an eye on Siya for her, Nonzuzo is worried that having so much time on his hands could be dangerous. In the short term she is encouraging him to join a gym and in January (the start of the South African academic year) she wants him to enrol in vocational short courses at a private college, even if she has to pay for them herself. She will apply for government funding, but it is not guaranteed.

Siya is upbeat about his future and is keen to train as an electrician. “There are opportunities for work in South Africa, but you need a skill,” he says.

Nonzuzo jokes that she is scared of electricity, before moving on to more serious matters. “I am hoping that in the next 10 years you guys won’t find us here,” she says. “We will have a house.”

She applied for government housing two years ago and is still on the waiting list. “You don’t choose where you live,” she says. “But you get two rooms with a bathroom.”

Wherever they end up, the photograph of the elephants will go with them. “I love elephants … They are so cool,” says Nonzuzo. “We have a saying in Xhosa, indlovu ayisindwa ngumboko wayo … I don’t know how to say it in English.”

An internet search reveals its meaning: “An elephant is not burdened by its trunk”– a person is not overwhelmed by their own responsibilities or problems.

Nick Dall in Cape Town